On March 3rd, my wife and I celebrated Hinamatsuri with our baby daughter.

Hinamatsuri, also called “doll’s day” or “girls’ day”, is one among the many beautiful traditions of Japanese culture. With preparations usually made over the preceding month, Hinamatsuri is an occasion to celebrate the health and happiness of young girls in the family.

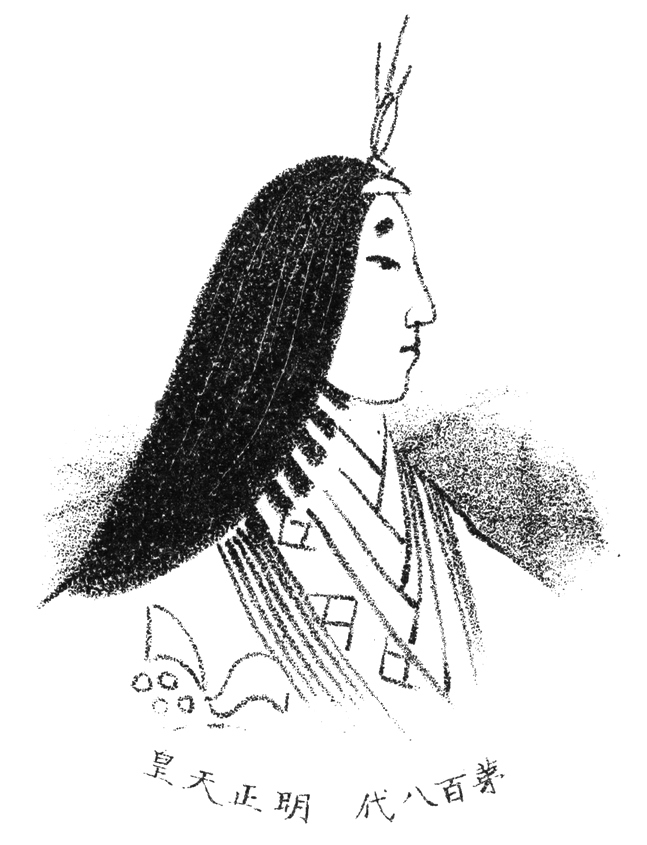

The good wishes are expressed through the consumption of specific foods and intricate displays of hina-ningyō (ornamental dolls) representing the Emperor and Empress, their attendants, and musicians in the traditional court dress of the Heian period.

Wait, let’s back up…How did this all start?

Legend has it that the practice began in China where small paper or straw dolls were used as a medium to offload and absolve people of their sins and misfortune. After rubbing the dolls over their bodies, they would then be set off on the river and float away into the ocean or the neighboring village; the point being that one’s sins were gone or quite literally swept away. These practices were emulated by Japanese aristocrats (and continues to this day in the Tottori Prefecture of Japan).

Hinamatsuri, as it is celebrated now, became fashionable during the Heian period (794-1181). The belief that one could absolve themselves of their sins expanded to include hina-ningyō and the dolls were forever symbolized as vessels for prayers of hope and prosperity.

As dollmakers got better and better at crafting hina-ningyō, their increasing prices, value, and quality also leapt correspondingly. Families no longer were keen on absolving their sins with the dolls and chucking them into the nearby river. Rather, the dolls began to be placed on show, with increasingly intricate displays.

The hina-ningyō were first recognized and used in the manner they are now as part of the Peach Festival, Momo no Sekku (as peach trees typically flower around this time), when Princess Meisho succeeded the throne following her father Emperor Go-Mizunoo, in 1629.

As female emperors were not allowed to marry, Empress Tokugawa Masako created a doll arrangement showing Meisho as being wedded. Hinamatsuri, as a festival, would officially become recognized in 1687.

So, how do we display the dolls?

It all depends on how many you have!

The entire set of dolls and accessories is called the hinakazari and can include up to fifteen dolls and various accessories for an enormous tiered display.

So, to start, the number of tiers and dolls a family can display depends on their budget. Generally, a set of the two main dolls including the Emperor and Empress is ample enough. The dolls are seated on red cloth amidst accessories that complete the representation of a Heian period wedding.

It is common practice for the dolls to be gifted after birth, with every girl in the family getting her own set of dolls. My wife was gifted her very own set when she was a baby by her grandparents (or my daughter’s great-grandparents). Our baby daughter got her own set (below) this year as a gift from her grandparents.

Enough about the dolls, what about the food?

My daughter asked the same question.

An assortment of treats are usually made for the occasion including Hishi mochi (multi-colored rice cakes), Ichigo daifuku (strawberries wrapped within adzuki bean paste), Sakuramochi (rice cakes with bean paste wrapped in a picked cherry blossom leaf), Ushiojiru (clam soup; the clam’s two sides fit perfectly to represent a strong marriage), and Amazake (sweet sake and non-alcoholic as we have kids involved).

-FYI, I felt real hungry as I wrote this-

Now, you don’t have to make all of this. It is difficult enough running after the little ones at home. Multi-tasking to make all these dishes, especially without assistance from other family members (as in our case, when our in-laws and immediate family live on the other side of the planet) would be a nightmare.

With our daughter mostly governing the house at this stage, we focused on creating one perfect dish, the Chirashizushi. This dish usually includes a combination of raw fish, veggies, and rice arranged in a bento box.

What happens to the dolls afterward? How about the boys?

Superstition states that the dolls must be put away the day after Hinamatsuri, as keeping them up any longer would result in a late marriage for the daughter. No worries here though, as this practice largely originated to protect the dolls from the rainy season and humidity that followed Hinamatsuri. Some families even keep the dolls up for the entire month.

Now, you may be wondering if this is “girls’ day,” what about the boys? Well, the boys don’t miss out as they actually have their own celebration a little later in the summer on May 5th, now known as Children’s day in Japan, but historically called Tango no Sekku or “Boys’ day.”

What’s the cultural connection?

I’m Indian and my wife is Japanese-Canadian, and we are very set on exposing our daughter to traditions from all three cultures. Whenever we discover a cultural parallel (and there are many), we are all the more excited to learn more ourselves.

In celebrating Hinamatsuri, I discovered that the festival and its Chinese counterpart share parallels with an ancient South Indian festival observed during the greater annual Hindu festival, Navaratri, in the honor of the goddess Durga. Known as Bommai Kolu, or Doll Festival, it is an occasion where young girls and women display dolls and worship the three Hindu Goddesses: Parvathi, Lakshmi, and Saraswati.

Much like Hinamatsuri, the Bommai Kolu is an occasion promoting creative expression for women and the fostering of family bonds, the difference being it is celebrated in the autumn festive season as opposed to spring.

What did we celebrate?

The family road so far has been a rough one for my wife and myself. As happy as we are in the company of our baby daughter, her birth came in the wake of a very difficult pregnancy, various health scares, and multiple hospital visits over the last two years.

Thankfully, our daughter is now hale and healthy, and living her best life while running an empire at home. She is our little queen with a big attitude, and an even bigger heart.

So, this Hinamatsuri we celebrated her good health for many more years to come, our happiness together as a family, and the joyful chaos she will be doling out on our lives.