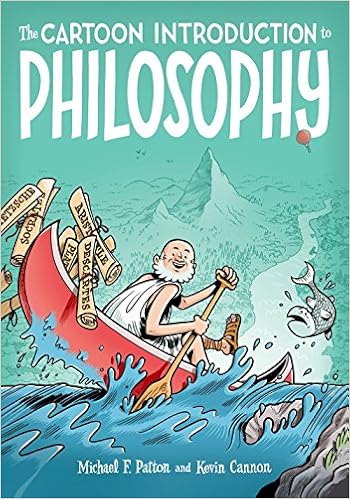

I love reading books, and especially so, when I’m sick. Last week was one such example when I endured a severe throat infection, spending my days doing the bare minimum of work that was necessary, and whiling away my remaining time alternating between bed-rest and pouring through the pages of my latest purchase from Chapters, The Cartoon Introduction to Philosophy, by Michael F. Patton and Kevin Cannon.

My discovery of this book was by chance and followed my efforts to purchase another philosophy text I have reviewed in the past in Luc Ferry’s A Brief History of Thought. Having read Ferry’s work, I had a pretty good idea of what to expect in The Cartoon Introduction to Philosophy, which as is obvious from the title, is a cartoon rendition of the great tradition of philosophy. Incidentally, it is also the subject of my first official review of a graphic novel, and what a wonderful read it was.

While the work may be considered moderate in volume, it more than makes up for this in the expansive content that it covers. In what serves as an engaging and entertaining read of the philosophical landscape, the humorous and instructive prose of Professor Patton dances alongside the pivotal illustrations of Kevin Cannon that ring true with the classic idiom, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

We are off to a great start as we get acquainted with our guide who is one of my favorites among the group of philosophers now considered as the pre-Socratics: Heraclitus.

Nicknamed “The Dark One” for his philosophical style, Heraclitus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher whose emphasis was on change and impermanence being the defining characteristics of our world as opposed to stability and balance.

Paddling alongside him on a metaphorical canoe, we set off on our journey through the long, and winding “river of philosophy.” Our adventures begin in the land of logic where we study the rules of reasoning and thought. Our travails are not an individual effort as we are joined by a fellow philosopher in Aristotle whose strict deductive relationships help us bridge our premises and establish the conclusion of our argument.

We loosen up a fair bit upon the arrival of a good friend from the future (there is a fair amount of time travel in the plot) in John Stuart Mill whose inductive reasoning paves the way for his generalizations about past events to predict the future.

Having learned how to assert and defend our beliefs, we look ahead to understanding what we know and how we know it. Our perceptions are brought to light through our skepticism that warrants a fundamental truth independent of all our senses in Descartes’ proposition that “I think therefore I am.” Descartes’ presumptions are subsequently set to a blank slate or the tabula rasa in John Locke’s empirical divisions of our world’s qualities, which are themselves ultimately laid to rest and grounded in the idealism of George Berkeley where the world is nothing more than a collection of ideas

This of course leaves us with no with no doubt that our perception of the world cannot be taken for granted, and honestly with more doubts than when we began our journey. Nevertheless, the dialogue continues as we traverse the realm of our minds, being as indecisive as we can ever be in finding our mind-body connection, before beginning to question our free will or the possible lack of one in the existence of God, and finally come to terms with our responsibilities and actions as we are driven by our knowledge of the world in ethics.

In what is a smart, witty, and up-to-date account, The Cartoon Introduction to Philosophy is a perfect starting point for any uninitiated reader in the pleasures of philosophy. Patton and Cannon have done a great job in providing a work that is sure to inspire the love and wisdom of learning or “philosophia” in both young and old. By the time we flip through the last page of the novel, it is obvious that our once metaphorical “river of philosophy” has now metamorphosed into an ocean comprised of various personalities, creativity, and a heck of a lot of thoughts in what is a gloriously concise compendium of a field of study that is its own protagonist.